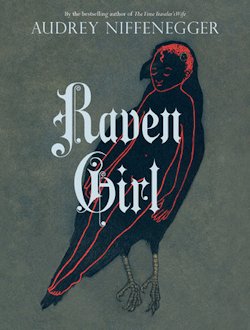

As oddly modern as Audrey Niffenegger’s third novel-in-pictures is in many respects, the story at its core is as old as the 17th century aquatint technique she uses to illustrate it. Older, even. In the beginning, boy meets girl. They become friends… their relationship strengthens… and in due course, a strange babe is made.

I say strange because it so happens that the girl the boy falls for is a bird: a fledgling raven who has fallen out of the nest. Seeing her, a caring mailman worries that she’s broken, so he takes her home, cares for her as best he can. What develops between them then seems straight out of a wonderfully weird take on Aesop’s Fables.

“The postman was amazed by the intelligence and grace of the Raven. As she grew and lived in his house and watched him, she began to perform little tasks for him; she might stir the soup, or finish a jigsaw puzzle; she could find his keys (or hide them, for the fun of watching him hunt for them). She was like a wife to him, solicitous of his moods, patient with his stories of postal triump and tragedy. She grew large and sleek, and he wondered how he would live without her when the time came for her to fly away.”

But when the time comes, the raven remains. As a matter of fact, she was hardly hurt in the first place; she stayed with the lonely postman for her own reasons.

Time passes. Magic happens.

In short, a child is born: a young human woman with the heart of a bird. Her parents love her utterly, give her everything they’re able. Still, she longs to share her life with others like her. But there are none… she’s the only Raven Girl in whole wide world!

“The Raven Girl went to school, but she never quite fit in with the other children. Instead of speaking, she wrote notes; when she laughed she made a harsh sound that startled even the teachers. The games the children played did not make sense to her, and no one wanted to play at flying or nest building or road kill for very long.

“Years passed, and the Raven Girl grew. Her parents worried about her; no boys asked her out, she had no friends.”

So far, so fairy tale. But Niffenegger does ultimately capitalise on the aspects of the uncanny at the heart of her narrative. Later in life, the Raven Girl goes to university and learns about chimeras from a visiting lecturer, who says the very thing she’s needed to hear for years. “We have the power to improve ourselves, if we wish to do so. We can become anything we wish to be. Behold […] a man with a forked lizard tongue. A woman with horns. A man with long claws,” and so on. It only takes a little leap for us to foresee a girl with working wings.

And so Raven Girl goes: right down the rabbit hole of body horror.

It’s a somewhat discomfiting turn for the tale to take, but soon one senses this is what the author hopes to explore: the book’s beatific beginnings are just a way of getting there. Thus, they feel slightly superfluous—an assertion evidenced by the lack of artwork illustrating the opening act. At 80 pages, Raven Girl is the longest of the three picture books Niffenegger has created to date, but not out of narrative necessity.

When Raven Girl finally takes flight, half its length has elapsed, but the half ahead is certainly superb. This may not be a fable for the faint-hearted, yet it stands a strangely beautiful tale all the same… of light glimpsed in the night, of hope when all looks to be lost. As the author attests:

“Fairy tales have their own remorseless logic and their own rules. Raven Girl, like many much older tales, is about the education and transformation of a young girl. It also concerns unlikely lovers, metamorphoses, dark justice, and a prince, as well as the modern magic of technology and medicine.”

It is this last which sets off the plot of Niffenegger’s new novel-in-pictures: the idea of science as supernatural after a fashion. Together with the muted elements of the macabre aforementioned, Raven Girl feels like kid-friendly Cronenberg, and the many moody aquatints very much feed into this reading.

No doubt Audrey Niffenegger is most known as the mind behind The Time Traveler’s Wife, but her latest emerges instead from the manifest imagination of the artist who produced The Three Incestuous Sisters, for instance. Like that dark objet d’art, Raven Girl is an insidious intermingling of words and pictures to be treasured: a beautifully produced, lavishly, lovingly illustrated fairy tale for the modern day—and very much of it, also.

Raven Girl is out on May 7th from Abrams

Niall Alexander is an erstwhile English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com, where he contributes a weekly column concerned with news and new releases in the UK called the British Genre Fiction Focus, and co-curates the Short Fiction Spotlight. On rare occasion he’s been seen to tweet, twoo.